Varusteleka Remote Military March

I was admittedly a lot less prepared for this march than I would have liked. My (somewhat stupid) attitude since walking the entire 180km “Icknield Way” in 79 hours in January has got me into the mindset that marching 25 or even 50km in a day is pretty normal — throw a few things into a ruck and go. While it might be a good attitude to have and the accompanying lack of preparation didn’t spell disaster, it meant I had nothing to eat beyond leftover freeze-dried meals and energy gels, didn’t decide on the route until 2 hours before setting off and had to carry a sense of shame along with me (the biggest legacy from my time as a reservist in the British Army is a steadfast commitment to “The 5 Ps”). Nevertheless, I still had a great time and relished the opportunity to get outside and embrace the suck.

Now, some of my choices might seem odd to someone unfamiliar with England (note: Scotland has a much saner approach towards the outdoors), so let me first elaborate. In the week leading up to the march I had considered travelling to a different part of the country: somewhere with better views, fewer busy roads and dense, all-encompassing forests. Somewhere that would indulge my curiosity. But after a little deliberation I decided it was too much — I had just returned from a multi-day, nearly 100km backpacking trip in the Scottish highlands where we climbed several 1,000m+ summits in snow, sleet, rain and hail. Not only was it hard to justify taking more time off, did I really want to drag my gear on a train or plane yet again? And what about water? If I really wanted to make this march 100% “self-supported” — no pubs or cafes like I’ve done on long distances in the past — I’d need a solid plan on where to replenish hydration. In this part of Southern England open water courses are hard to find and even harder to access, so you often have to rely on taps in churchyards. And did I mention that wild camping is illegal?

So it was decided: cover terrain that I knew and reduce travel to a minimum; focus on marching without any unnecessary cognitive load. I prepared a number of rough routes, but would leave it up to the weekend’s workload (I run my own company) to decide whether I would do the full 50km or the half. The only certainty was that I would bivvy the night and march back again the next day - that I would not compromise on. For this reason every potential route incorporated a known spot where I’ve camped in the past.

Owing to messed up trains (a common occurrence in the UK) I didn’t make it home on the Friday until after midnight, got up later than I’d liked and started my usual Saturday morning work “chores” by about 08:30. The time ticked away. And ticked. And ticked. Just before midday, I decided that if my march was going ahead, I needed to get going. I settled on a 25km route — assuming 6-7 hours of walking (including breaks), I would aim to arrive and pitch up just as darkness was setting in. I quickly got packing and at 14:45, I walked out of Harlington station and hit start on my Garmin relishing the warm sun and the cool breeze.

The first few clicks out of the village and across open fields to the foot of the chalk escarpment were easy and enjoyable. "This weather is too good for a military march", I thought. I climbed the steps up and over the old chalk quarry or ‘pit’ with only a little strain and along the winding path at the base of the ridge, stopping only at brief points to snap a photo each time my watch signalled another kilometre had passed. Further along I climbed the long, gradual steps to the top of the ridge, turned left and marched on through the woods and sheep fields at a very good pace to my first destination: Sharpenhoe Clappers.

This is the very northern edge of the Chilterns, and below the steep drop a low, flat plain stretches almost uninterrupted to the North Sea. The planned route would meander up and down the escarpment in a very indirect 25km, passing sites that reveal the ancient history of the area — and the trackways — to arrive at Telegraph Hill, one of the highest points around and a place with a unique military history. The Clappers itself is an Iron Age promontory fort surrounded by steep drops on three sides and the remnants of a manmade defensive wall to the south, and when viewed from the north it looms large on the horizon for miles. Despite all of the spectacular places I’ve been throughout the world, this remains one of my favourites.

I dropped my pack briefly to sit and watch the lambs enjoying the first days of spring (and their lives!) in the fields below, but the combination of far more people than usual (the place is relatively unknown which adds to the special qualities) and my good pace made me reluctant to stay. So I pressed on, stopping further along the ridge to quickly eat one meal and prepare another for later. I passed through the village of Streatley, across a busy road and back out into the fields, interrupted only briefly by an older woman who asked where I was headed. Telegraph Hill “isn’t far” she said — “if you are walking straight there” I thought to myself.

This area is a boring and uneventful collection of fields and power lines, but with decent tracks the progress was good. I crossed the ancient path of the Icknield Way (which from here continues straight for only a couple of km to my destination at Telegraph Hill), went over an empty golf course, and pushed on up the steep heathland onto Warden and Galley hills — the site of many ancient burial mounds and a triangulation (or ‘trig’) point. I paused momentarily to spot the house where I grew up on the opposite side of the valley; Sharpenhoe Clappers and Telegraph Hill are also visible from here.

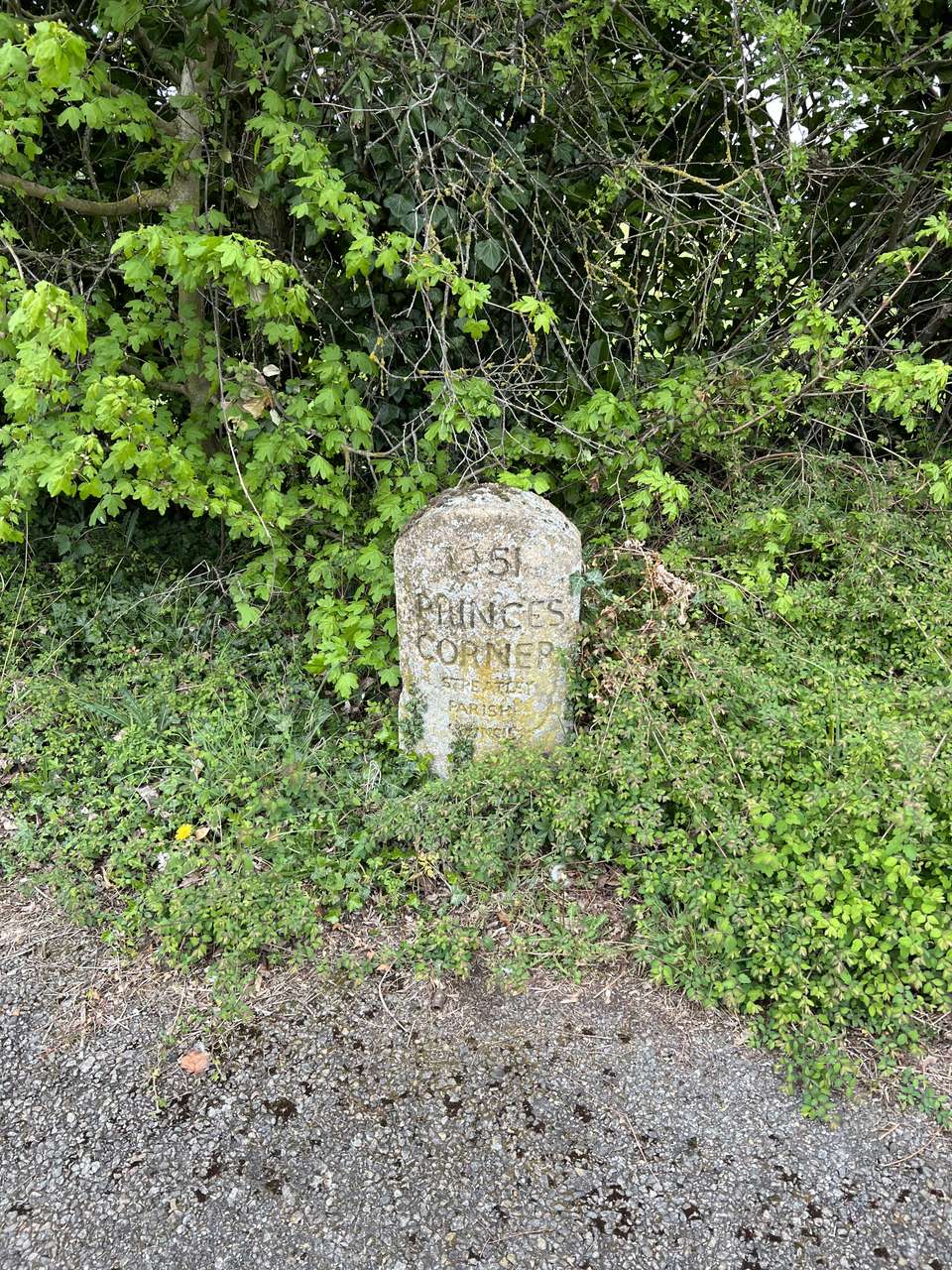

I had long since decided to continue without stopping until I reached the village of Hexton at the 20km mark, but was curious about a private estate I would be passing through close to the village — an area I hadn’t visited before. Dropping down on the path behind Warden Hill before strenuously regaining the elevation, I headed up a farm track that leads almost exactly due north, passing a handful of runners and re-crossing the Icknield Way no more than a kilometre further on from our last meeting point. I walked on through the yard of Mortgrove Farm, an old but carefully maintained collection of buildings and horse paddocks, and out onto Barton Hill Road for around 150m. Even at this short distance this kind of country back road can be dangerous for walkers and is the primary reason I use a blaze orange backpack cover.

Back into farm fields, I was now on the estate that had drawn my curiosity. Here amongst the trees that cover the continuation of the chalk escarpment stands the site of Ravensburgh Castle, another ancient hill fort that exploited the arrangement of steep natural defences to, legend has it, upset the Romans:

"Ravensburgh Castle is one of the most important and significant of all the Iron Age hill-forts, the largest in eastern England … thought to be where the British mounted a heroic resistance to Caesar when he invaded.”

Little of the castle is visible from the track due to the thick woodland, and venturing into the steep surrounding ravines would unfortunately be trespassing. But other clearly manmade ditches drop abruptly away beside the public path, and I enjoyed sharing these peaceful and impressive surroundings with a pair of roe deer who were startled by the lone figure marching down the steep path through the trees.

Back onto another narrow road and carefully across the “main” road, I had reached Hexton. I snapped a few photos of the unique signpost-cum-water pump at the crossroads and took the short detour off my route to the village church. I was relieved to find that the tap I’d seen in photos during my limited research did indeed exist and spouted deliciously cool water, so I stocked up with three litres for the night and took a seat on a bench to eat the (now cold) freeze-dried meal I had prepared earlier. In truth, I was thoroughly enjoying myself and excited to camp out under the stars.

I lingered a little longer before setting off through the village. Rounding a series of open fields and clumps of trees (or ‘copses’) past a nicely secluded house with a water mill, it was dark when I made it back onto the same "main" road at the village of Pegsdon, about 1.5km directly west from our previous crossing. From here a 4x4 track gains around 100m of elevation in 1.3km to the top of Telegraph Hill, where we would once again meet the Icknield Way and the dense woodland known as Hoo Bit — our home for the night. I followed the initially gradual incline, the dim lingering sunlight making navigation with a torch unnecessary. With just under 300m to go the track became extremely steep, before I finally met my finishing point at a dishevelled-looking kissing gate where I stopped my watch 6 hours, 33 minutes and 31 seconds and 26.66km after leaving Harlington.

There was a steady wind at this elevation, and the haze and spots of low cloud meant I could barely make out the red lights of a radio tower in the distance and little else, but even in poor visibility it’s easy to see why it was chosen as the location of a semaphore telegraph station during the Napoleonic wars. I retraced my steps back along the track to just before the steepest section and cut into the trees.

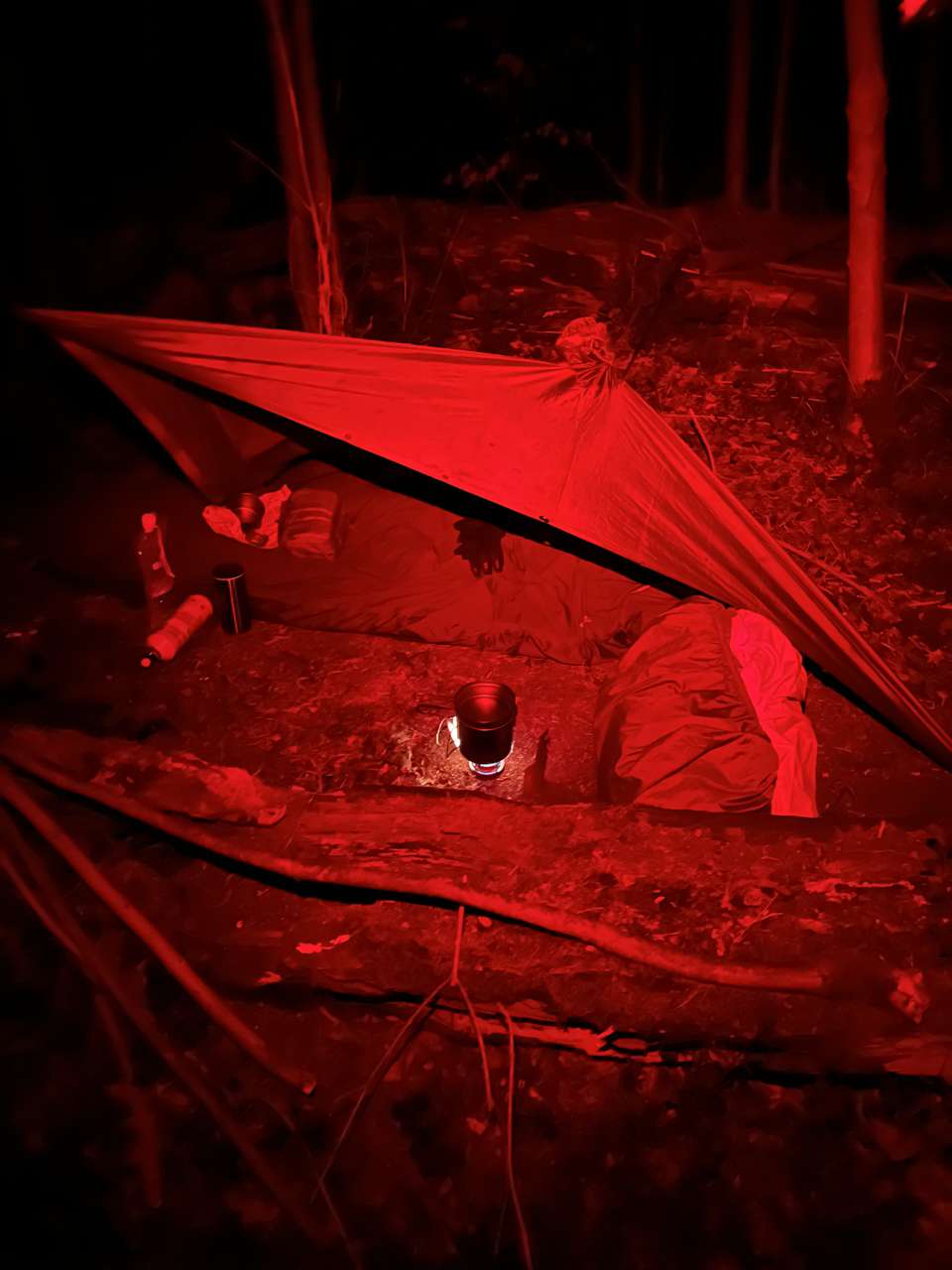

The last time I’d camped here the ground was barren and the trees were bare. This time the encroaching nettles made me tread carefully to avoid getting stung through my thin pants. I located my “old” spot within a dense line of hazel and sheltered by two long fallen and rotting sycamores. Awkwardly, the wind was blowing straight in from the unprotected north, so I cleared the ground and set up my rain poncho as a makeshift shelter to shield where I would bivvy and cook. This proved so successful that I never needed to wear my insulating jacket.

I’d finally got my mat inflated, Trangia going and sat down on my bivvy bag when to my surprise a fox started barking only metres from my position! I stood up but by this point it was too dark to make anything out, and after a long pause it started up again, this time further down the hill, whereupon another chimed in. “Warning his mates” I thought. No owls this time.

After I’d filled my flask for the morning, had a hot drink and taken the customary before-bed leak, I settled into my bivvy bag just after 11pm. The dense high cloud had cleared, and between patches of fluffy low clouds I got glimpses of stars — a welcome reward and one of the best parts of eschewing a tent. I drifted off to thoughts of why this always felt like a special and welcoming spot, the many travellers who must have passed through here over thousands of years, and

By 05:30 I was snoozing lightly to the bright and noisy morning, the birds keen to get me out of bed. I took my time to make coffee and porridge, and walked back out to the track to see whether it was worth venturing further west to Deacon Hill and its uninterrupted sunrise views. Dense cloud meant it wasn’t, so I relaxed for a while back at my campsite and watched early morning runners and hikers pass by on the track. I rehydrated a meal of pork to stock up on calories, made another round of coffee in the flask, and got a few energy gels ready before packing up and clearing any evidence of my presence.

By 08:00 I had walked back past last night’s finishing point at the kissing gate to look across the hills that make up the bulk of the nature reserve, and was ready to set off on the return trip. Although I wanted to enjoy the morning outdoors, I decided that my priority was to head back as quickly as possible and get on with my work. Less photos and less exploration. Within an hour I was back at the church and refilling water, making sure to drink plenty and carry the bare minimum. I pressed on, once again regaining the elevation and shedding any grogginess on the path through the trees near Ravensburgh Castle. The farm tracks that followed made for easy going on the way back to Warden Hill, my only setback being a short detour into some woods to go to the toilet as there was so many people around.

I skirted round the back of the hill, noticing there was a much clearer view of the opposite side of the valley today, but didn’t care to stop. A handful of dog walkers were out, and the golf course was that busy that I had to wait to cross the fairway. I decided to take a brief pause in the plantation that lines the Icknield Way to boil some water for coffee and another two meals, with my aim being to pack up and move on so that I could walk during the 15 minute rehydration time rather than sit and wait. So I was annoyed when, 30 minutes later, I was still sat waiting for my water to boil. Don’t get me wrong — I much prefer cooking on a Trangia-type stove because you can actually cook real food and the environmental impact of gas canisters is horrific. But I have had occasions like this where — despite sitting in blazing sun with no wind at all — it takes all day to boil a pot of water. When I was finally done, I packed up as planned and was back on the trail over an hour after I’d stopped! I resigned myself to eating while walking.

No more than an hour later, I’d recrossed the busy road, passed through Streatley without bumping into yesterday’s local, and was back at Sharpenhoe Clappers. I retook my customary spot looking out across the sheep fields with my route and final destination of Harlington in the distance. Today was the busiest I had ever seen it here, with large family groups and cars lining the road outside the jammed carpark. Many of these people looked as though they were out of hibernation for the first time since last summer — what an odd sight this lone marching figure with a large military backpack must have been.

By now I had really picked up the pace, angry that after such an unnecessarily long stop I was unlikely to beat yesterday’s time even with less ascent in this direction. This feeling quickly dissipated when, at a large field full of sheep and their newly born lambs, a small ball of wool came running towards me. I stopped momentarily to record a video and reminded myself that even on a “military march”, my number one job was to enjoy it.